DRAFT 1

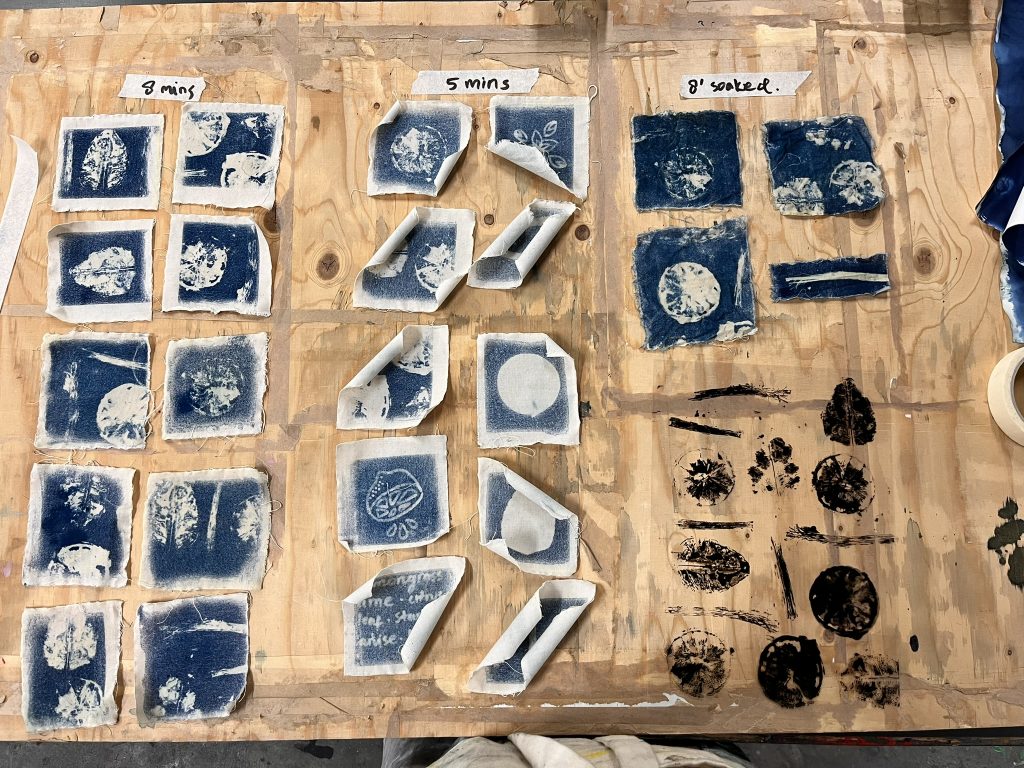

From desktop research, I already knew that different exposure time yields different results in cyanotype. However, by doing it on my own I realize that the difference in exposure time must be quite extreme to find different results. Not to mention, I was using an LED UV box usually used to make screens for screen printing, instead of using actual sunshine. Gauging how long it takes to develop the prints is an arduous process, and I didn’t expect that I must widen the interval this much. As I am writing this, I haven’t successfully captured the details in the specimens I’m printing.

Another challenge that I found is how the LED UV box shines from below instead from above, so having thicker, more three-dimensional specimens (like star anise and lime slices) became a hassle. I am determined to find a good way to print these specimens with the machine I am using.

With the technique I’m using right now, it seems like the process I have been doing favors the exposure of clear films instead of specimens. With my experiments of using acetate and drawing on them, I could get a good result with just five minutes of exposure. But, since cyanotype is used mainly to archive biological specimens, I am determined to find a way to use it to document the herbs and spices I have. I think the archival nature of cyanotype could be used to archive something beyond the specimens being printed, through a collection of printed specimens.

I’m mainly going to try to do multiple exposures. I think it could be used to show movement and maybe show different tones of blue in one cyanotype.

DRAFT 2

On his lecture about iteration, Matthew Crislip mentioned “guessing and knowing” in the context of iteration. He mentioned that while iterating to refine something to get to a singular output, that desired output is a hazy vision from guessing and knowing the process. From what I’ve learned about cyanotype, I know that the longer it is being exposed to UV, the bluer it becomes once developed. Bearing this in mind, I’m guessing that I could create a print with different tones of blue by exposing the material I’m using multiple times.

The initial trial holds on to the full process of cyanotype, repeating the act of coating, exposing, and developing multiple times. The outcome is not what I had in mind, getting little to no difference in blue tones.

Then I am reminded of analog photography, and how I could intentionally jam the mechanism of my camera to force the same frame to be used twice. I copied this process, exposing my material twice with different objects and then rinsing to develop it. This produces a better outcome resulting in distinct and crisp blue tones.

The process of exposing the same material twice brought a new question: how many exposures can one material take?

To avoid randomness, we must establish a logic for this process; constrains to sharpen the perspectives. (Andrew Blauvelt, 2013) The UV exposure was established as the control variable, since it is the same UV index every exposure and by establishing a standard set of time for each exposure, it has become the logic for this process. Additionally, there is the constrain of overexposing the material. It is just a matter of input.

Establishing this logic opens the multiple exposures process to many different possibilities. Through iterations, I have found the timing for double exposures on paper would be 3 minutes on the first object, and 2 minutes on the second. However, to do more than two exposures, the time needed per exposure is 1 minute and 45 seconds to ensure the shape of the first exposed object is still visible after the third exposure.

However, this logic is not yet perfect. I have been working with the working theory of addition; changing the objects every exposure to produce the final print. With the nature of more UV exposure equals darker blue, I wonder if instead of addition I should be working with subtraction. This could mean layering all the objects I would like to print and taking away elements of it on every exposure. This could produce a more predictable outcome.

DRAFT 3

Cyanotype was the first successful non-silver photographic printing process, invented by Sir John Herschel in 1842, originally as a way for him to copy his notes (Herschel, 1842). It has been widely used to copy floor plans and other technical drawings needed in building, hence why we have the term ‘blueprint’ ever since. This very precise and exact nature of the outcome is cyanotype’s strong point, besides being very beginner friendly and inexpensive, is what makes it a good tool for copying and archiving. Take Anna Atkins as an example, who used cyanotype to document her collection of seaweed into one of the first photographic books. (Atkins, 1853)

Working with this historical background, two things are established of the nature of the prints: it is very precise, and its strong point is to document or archive. But what if what being documented is not the object being printed? Then, would the exact and preciseness of the object matters?

Since the nature of the chemicals used in cyanotype is it gets bluer with more UV exposure, an educated guess was made that multiple exposures on a single material will create different tones of blue without any alterations on the objects being printed itself. This decision stems from how cyanotype is regarded as a form of camera-less photography, and how in analog photography it is possible to do multiple exposures on the same frame of film that will create a layered photograph. Building on the system that already exists on a different format (Jencks & Silver, 1972), the iterative process of fitting the system into the cyanotype format involves a lot of fine tuning that happens as needed as the process goes on to achieve a layered look that is not traditional in cyanotype. These different tones of blue, the layers of objects being printed on one material, it all intertwine in a way that it creates a new thing instead of being the sum of these layers.

The Many Shades of Blue is a documentation of the journey, not exactly a line of codes that could be used to replicate a multiple-exposure cyanotype print. Instead of an exact replication, it is inviting people to go through the process of refining the multiple exposure cyanotype process. It is a diagram to show not only how to “correctly” do multiple exposures on cyanotype, but also to show how to do it “incorrectly”. It poses no right and wrong way to do this, only showing what the outcomes could be in hopes that every outcome could be embraced. It is easy to get adhere to the binary system of success and failure, so this diagram hopes to show how it is not at all binaries (Halberstam, 2011). There is no right or wrong way, there are just many ways that give many different outcomes. It poses all outcomes as they are: an outcome, instead of assigning them as being the “correct” outcome or the “incorrect” outcome. It builds on the idea that there is no one definite solution or outcome, just a set of solutions that is suitable for different situations (Andrew Blauvelt, 2013).

By positioning itself as a diagram, it is trying to be your launchpad. It is trying to be your starting point, the general ballpark of how to do this process that is highly explorative. It invites you to build upon it, iterate further upon it, introduce your own subjectivity to it, and create something that is more than the sum of its layers.

Works Cited

Andrew Blauvelt, e. a., 2013. Conditional Design Manifesto. In: Conditional Design Workbook. Amsterdam: Valiz, pp. ii-xiv.

Herschel, J., 1842. On the Action of the Rays of the Solar Spectrum on Vegetable Colours and on Some New Photographic Processes. London: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London.

Atkins, A., 1853. British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. s.l.:privately printed.

Halberstam, J., 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. In: Introduction: Low Theory. Durham and London: Duke University Press, pp. 1-25.

Jencks, C. & Silver, N., 1972. Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation. Cambridge: The MIT Press.