Reflection

I’ve always wanted my practice to center on human experiences and humanizing our existence in the world. This project helped me develop that focus. Early group discussions and learning about Crip Time highlighted how challenging it is for disabled people to keep up with everyday life. We chose to explore corporate culture—specifically, the rigid 9-to-5 work system—which often excludes disabled people. This led us to question what it means to be “productive.” The frequent association of productivity with profitability felt dehumanizing. Should we even aspire to be “productive” if it simply means generating profit for others?

I believe resistance to this system is necessary—not to completely dismantle it (that might be too optimistic) but to show, on various scales, that employees are human first. Our project could be a form of resistance, but it’s also important to recognize that each time a disabled person listens to their body instead of pushing to be productive, that too is resistance. Moving forward, I’ll continue resisting this system through both my attitude and my design work, advocating for a more human-centered approach.

Works Cited

Harney, S. & Moten, F., 2021. AL-KHWĀRIDDIM: Savoir-Faire is Everywhere. In: ALL INCOMPLETE. Colchester/New York/Port Watson: Minor Compositions, pp. 55-60.

This text is what started this project; acknowledging what The Killing Rhythm is and how it is so deeply embedded in our life that we don’t realize that it is there anymore. In our project, we identify the 9 to 5 work hour model as a Killing Rhythm. It is interesting how much it fits into the description Harney and Moten made in the text, and how the more we develop the project the more it is obvious that it is a Killing Rhythm; how it establishes itself as the only rhythm, how the ones inflicted with it actively tries to develop it, how it is inflicted upon individuals that soon inflicts the same harmful thing to individuals that comes after them. We really wanted to put a focus on how it is never ending, the nature of this work hour system that keeps going like a never-ending assembly line where the assembly line itself is the product it assembled.

Waerea, K., 2024. On Crip Time. [Art].

In the publication On Crip Time, we explored how differently one would go through their day if they are disabled. There are so much things to consider, so much decisions to make. It puts into perspective of how much effort it takes for a disabled person to keep up with the rhythm of the world, and in the context of the Killing Rhythm that has been established beforehand, we soon find that most disabled person detailing their experience has expressed how hard it is to work 9 to 5, and in extension, staying productive. This sparks a conversation that challenges productivity and what it takes to be productive, a theme that is visible in a lot of our iterations. We soon identifies that the notion of productivity is merciless in the way that it doesn’t care about what kind of disability you have—you don’t even have to be disabled. As soon as you are deemed unproductive, no matter the reason, you are branded as such, making you at risk of being kicked out of the system.

CRIP TIME. 2024. [Film] Directed by Carolyn Lazard. s.l.: s.n.

Similarly with Waerea’s work above, this film further illustrates the experience of crip time. It is not just about being slower, it brings complexity into the topic. We acknowledge that while most if not all disabled people experiences crip time, how they experience it is different between each individual. It is not a one size fits all, and it makes us come into the conclusion that if we cater to one type of experience, there will still be a lot of people that are excluded. This conclusion solidified our decision to focus on the 9 to 5 work hour system and productivity itself, instead of a certain type of disability. We believe if we address the system and what is wrong about it, we could have a wider reach instead. We chose to highlight the efforts it takes to stay within the 9 to 5 work hour system, however way that takes form. This highlighting and forcing recognition on efforts is a key step in our iterations.

Daniels, A. K., 1987. Invisible Work. In: Social Problems. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 403-415.

On the topic of what kind of work is being recognized and what isn’t, Daniels has explored it through the gender lens in her essay Invisible Work that has been substantial in conversations about women in the workforce and feminism. We draw parallels in the work women put in to maintaining a household and caring for a family with the work employees put in to maintain productivity (or even just the optics of it). In the text, Daniels wrote how recognition of work gives it importance, and in our society this recognition comes in the form of money. The monetary value gives certain labour more importance that other labour, even though the less valuable labour is necessary to ensure valuable labour could even happen. Through our later iteration, we force recognition for these undervalued labour through visual experiments instead of putting a price tag on them. We forced the idea that both kind of labour exists as two sides of the same coin that interacts and interrupts each other in more ways than we realise.

Blauvelt, A. et al., 2013. In: Conditional Design Workbook. Amsterdam: Valiz, pp. ii-xiv.

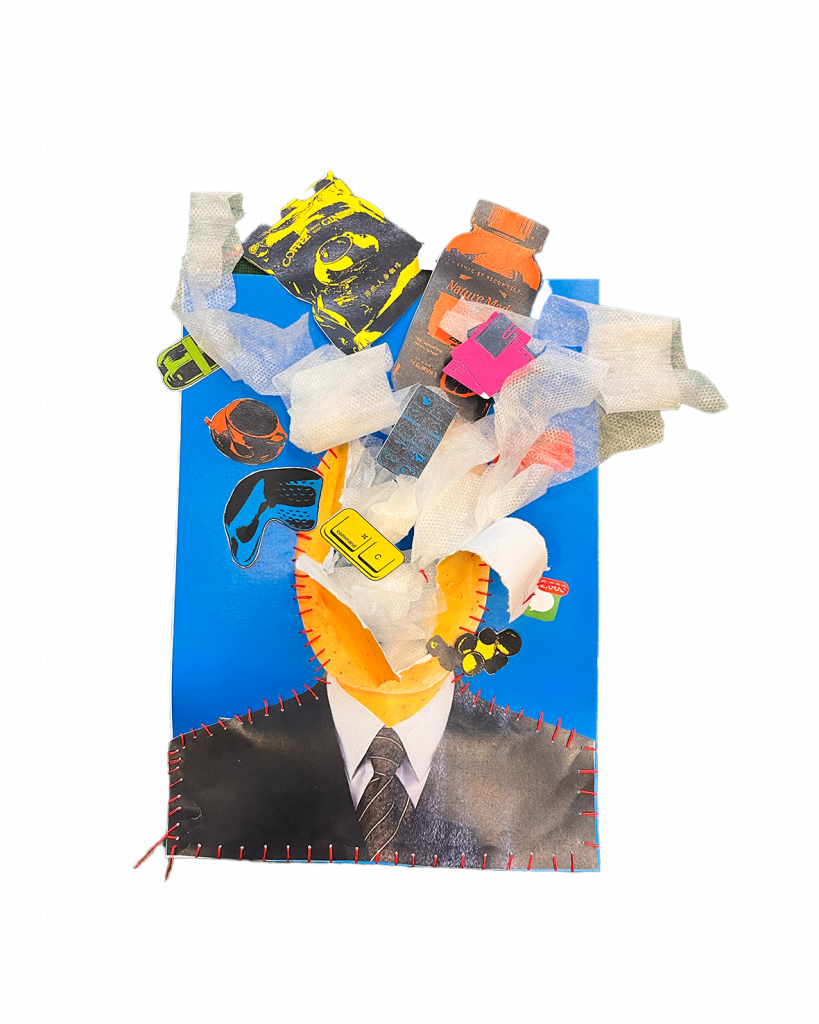

The way this project is developed is in line with the conditional design manifesto. The conditions that was set were hiding and changing the narrative through interaction with the medium. Within these conditions, we continuously iterate, allowing the message to emerge in a way that cannot be ignored. We have variables that continuously appears in each iteration, such as the potato, the process, the items representing efforts to stay productive. These variables gone through permutations, we present them in various ways to make sure the message we want to tell not only stay visible, but is loudly and boldly stated. Although there is a question of reproduction that we couldn’t explore due to constrains of time and resources. Even though we didn’t come up with a program that becomes the output of our process, our experience of iterating the project is arguably in line with The Conditional Design Workbook.

Bolt, B., 2021. Beneficience and contemporary art: when aesthetic judgment meets ethical judgment. In: The Meeting of Aesthetics and Ethics in the Academy: Challenges for Creative Practice Researchers in Higher Education. s.l.:s.n., pp. 153-166.

In our project, we intentionally create tension and discomfort by using methods like stitching on paper and making concertinas that are intentionally difficult to handle. On one of the iteration, we put filling inside a poster and stitched it shut. Afterwards, we invite the audience to rip the stitching apart and expose the fillings as a way to show that no matter how uncomfortable and inconvenient, efforts must be recognized. The presence of provocation and discomfort while interacting with art is not new to me as I have always been using art as a tool of protest and resistance. It is good to know that moving the realms of arts, we are able to employ discomfort as a tool to move people and get our message across; although letting the audience know beforehand about the discomfort that they about to experience is something that I should keep in mind as practitioner moving forward.