In a recent post, I have talked deeply about my findings in St. Pancras Garden. Admittedly, at first, I was confused as to what to do with it, since it isn’t a very dynamic site. It felt like I was just sketching and reading, not much I could do with an object that just stood there, unchanging and steadfast.

So, I talked with Juliana, who offered some great insights but most importantly asked the question that spurred me into motion: what is a memorial?

A memorial is a structure established to remind people of a person or event. In this case, the memorial was commissioned to commemorate the people whose graves were disturbed in the building of the railway (I talked a bit more about this in the last post, if you’re curious). As years go by, these people are reduced to just names carved onto limestone. Sure, we can look up their names and read their stories, but there is a certain level of disconnectedness between their names on the monument and their stories floating around the internet and other archives. Not to mention, centuries have passed since they roamed the earth. There is a feeling of folklore when their stories are being told as if we (modern-day people) couldn’t fully grasp that they were people just like us.

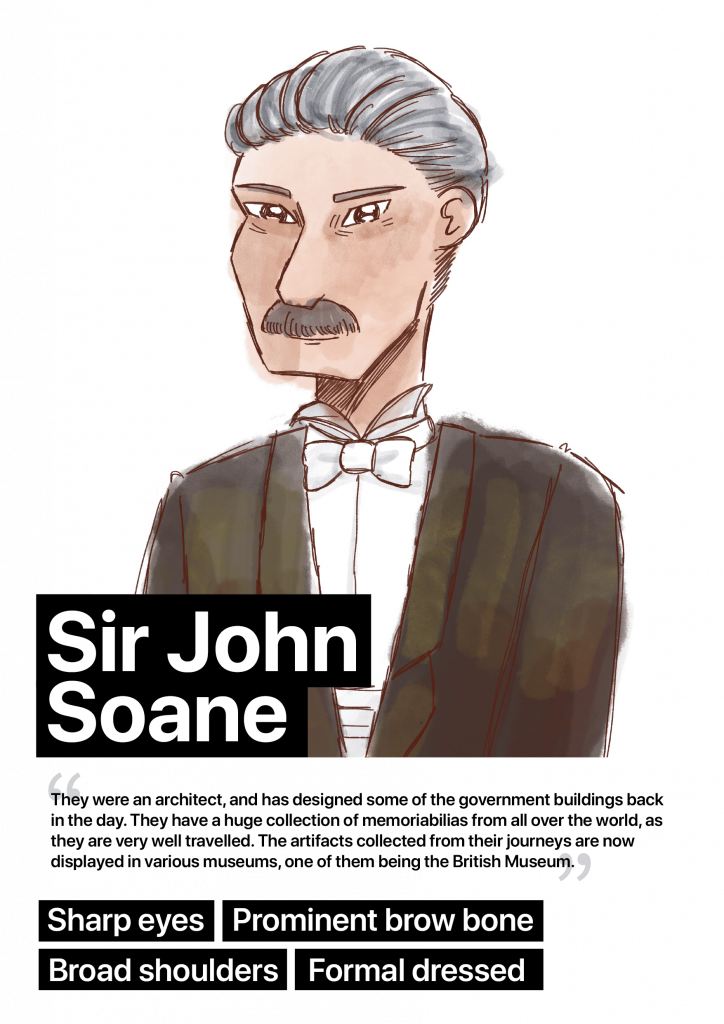

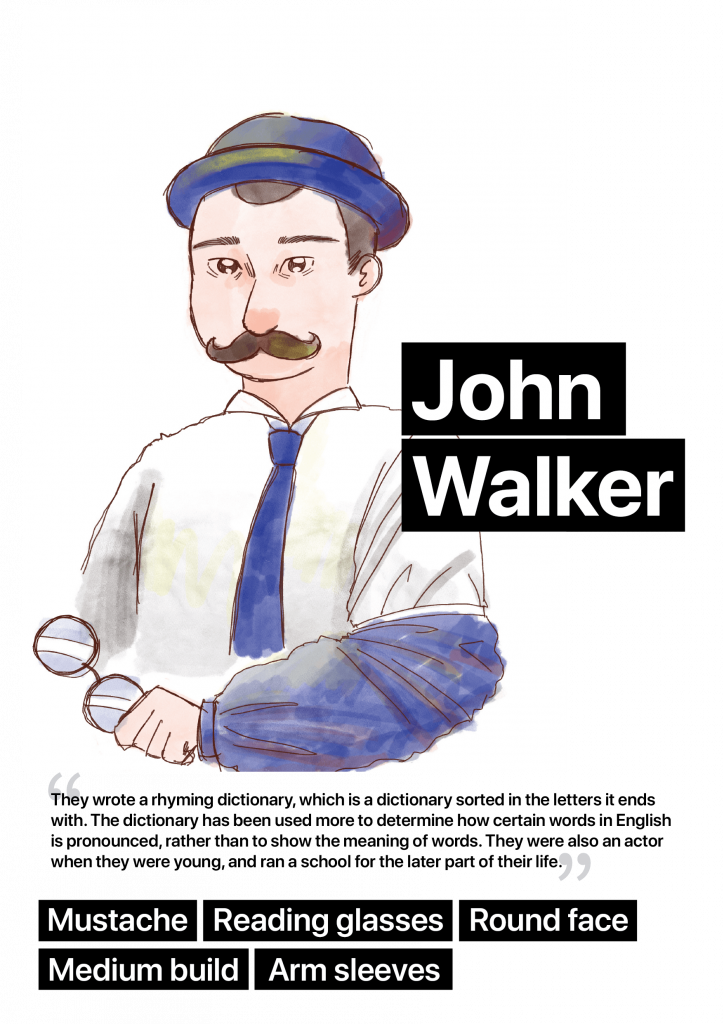

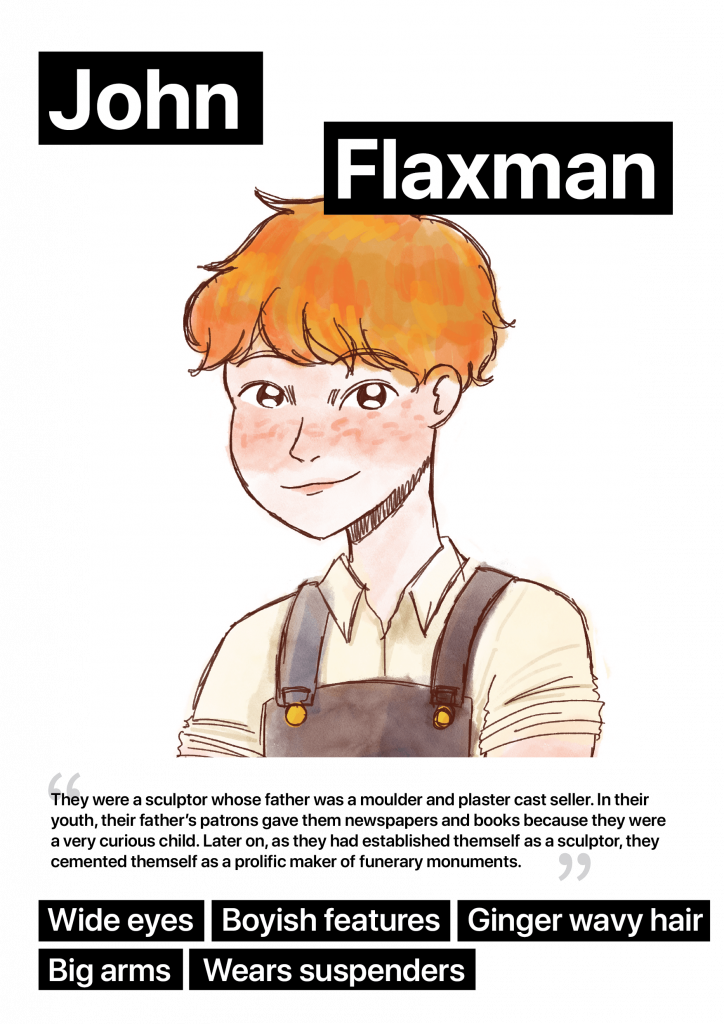

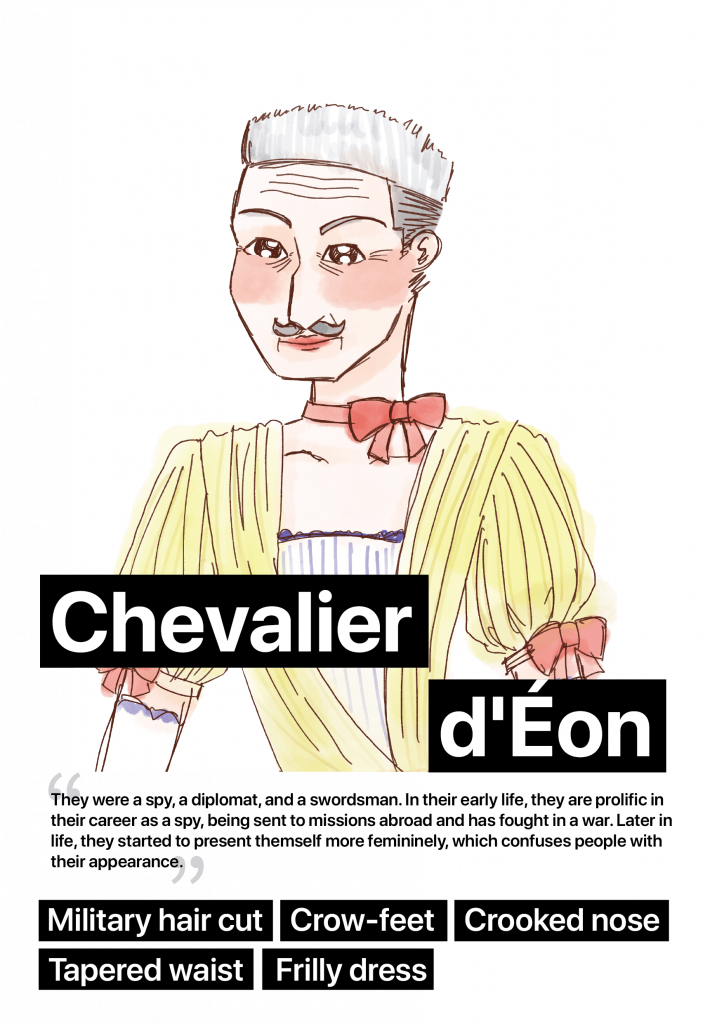

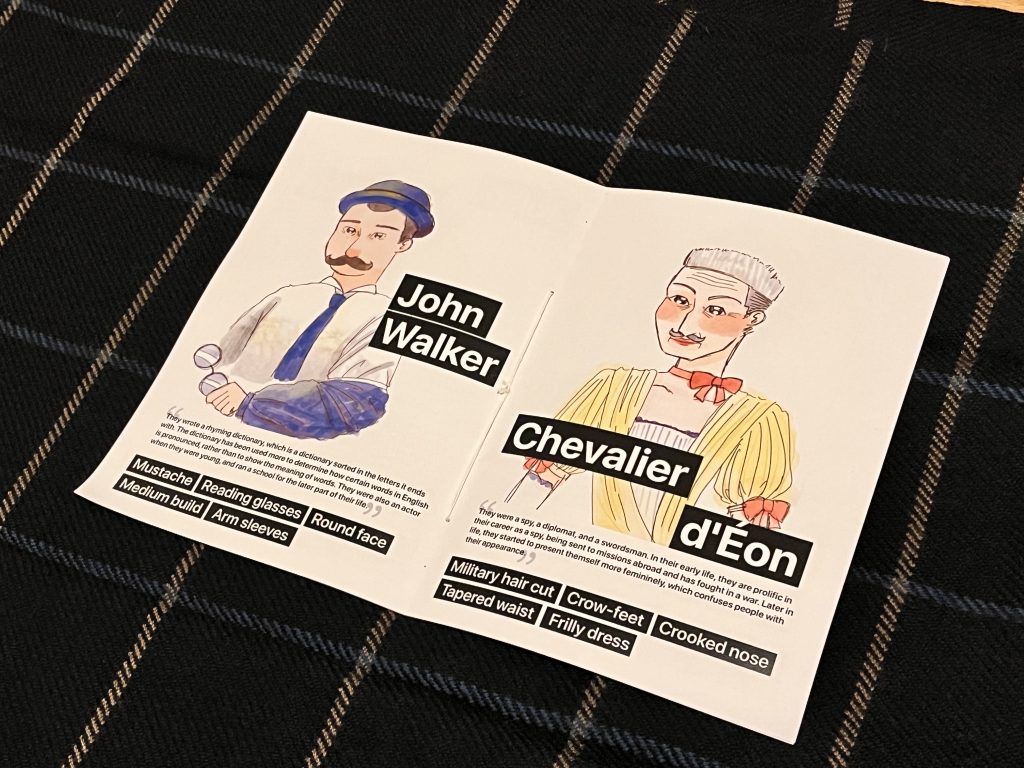

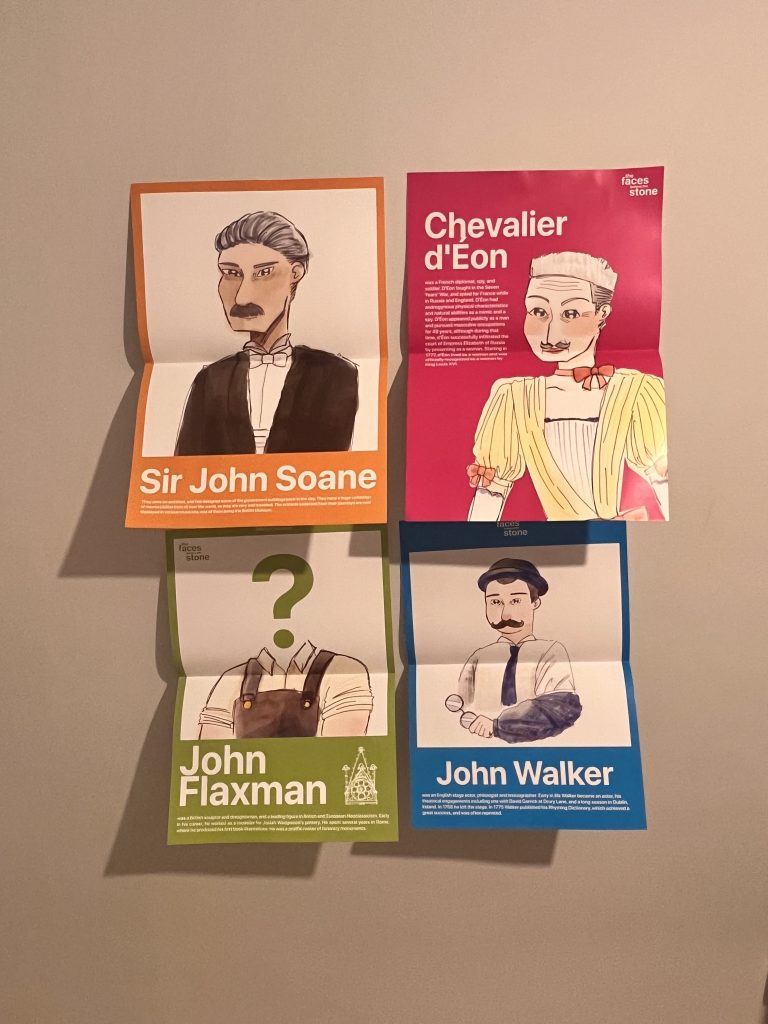

I set out to tell their story, but in a way that is engaging and could make the stories stick more in someone’s memories. I noticed that there aren’t many depictions of Sir John Soane, John Walker, John Flaxman, and Chevalier d’Eon, so I invited my friend to imagine how these people looked like, as I was sketching them based on her description.

My tutor, Houman, pointed out a good question: why do these stories need a face? Why are their faces important?

I think faces are important to humanize the person behind these stories, to differentiate them from fiction or folklore, emphasizing that these are real people. Inviting my friend to imagine a face for these people also forced her to slow down while digesting the story I was telling. It forced her to stop at every detail of my words, pick up things spoken between the lines, to visualize a person she could match with the story I was telling. This makes the story more memorable to her, too. If the project fails, at least I have told the four stories to one person to keep it alive.

My method was this: I told my friend, who is an Indonesian woman who recently moved to London (so totally outside of the community to which these people belonged), the story of each person, without mentioning their age, race, or gender. I mostly told a story of what they do, for example for John Flaxman I told a lot about how he came to be a sculptor. For Sir John Soane, I emphasized the vast collection of artifacts that he acquired through the years, while for John Walker I talked a lot about how he wrote a rhyming dictionary and what it is. As for Chevalier d’Eon, I talked more about their gender expressions, as well as their occupation in the military.

The results were fun to dissect, at least for me.

From the get-go, my friend concluded that this person was rich, so she requested a sharp-looking tuxedo and slicked-back hair for them. She also said that this person must be well-traveled, so he must have been healthy, which translated to broad, sturdy shoulders for her. She also said that this person should have sharp eyes and prominent brow bones. Perhaps this is connected to how they have a keen eye for artifacts and memorabilia?

“This person must had a lot of free time,” My friend said as soon as I finished telling the story. “Who else would have the time to make a rhyming dictionary?” I asked her if she think he is well-read, and she said that he must have known a lot of words, but not enough to be able to write a novel or a book. She settled on giving him reading glasses. Arm sleeves are also a must, according to her, as this person struck her as someone who was of the working class. His features are soft, not at all striking, just a regular man with a mustache and round face.

It is interesting to see the sketch of John Flaxman turned out to be the most youthful of the four. I think this is related to how I talked about how he was curious as a child, how he would become a sculptor, and briefly about his relationship with his father. My friend gave him big wide eyes, probably because he was a curious child. I could imagine him looking around the world around him with those curious eyes. As he was a sculptor, my friend thought that this would translate to him having big arms, despite having a lean body. The ginger hair and freckles, I think, add to the boyishness vibe of the entire story.

For this one, my friend kept asking me about gender, as I described someone who was a swordsman and a spy who had a penchant for frilly dresses. I stood my ground and told her nothing about their gender. Their early career in espionage and the military gave my friend the idea of having a military boxy haircut, as well as a chiseled jawline and chin. As for the crooked nose, my friend argued that they must get punched a lot, so it made sense if their nose was crooked. She also requested for this sketch to depict them as older, with smile lines, crowfeet, and lines on their forehead. Perhaps, there is a sentiment of wanting to see obviously queer people grow old with obvious signs of having smiled a lot.

I made these sketches into one publication, thinking that it could be given out to the people who walked around the sundial monument. But then I thought that a publication may be too much information to digest for someone who is just out for a casual walk, so I made some folded posters as well. I wanted the poster to look white and plain while folded, but vibrant when opened. The vibrancy of the colors kind of leaked out when folded, too, giving a suggestion of something inside.

All in all, I think this whole process has challenged me to use methods I’ve never used before to investigate. History is not something that strikes me immediately as visual, so it is interesting to see how we can visualize history like this. My groupmate Charlotte also pointed out that this fun activity could be expanded by giving out zines with just the stories written on them, challenging the readers to draw their own version of the person behind the story. I think there are potentials I haven’t fully tapped into with this method, too.

Moving forward, I am torn between giving more details visually on these four people or moving on to other people’s stories which are yet to be told, currently trapped inside the stones of the Burdett-Coutts Sundial.